, progressive modernism came to dominate the art scene in Europe to the extent that conservative modernism fell into disrepute and was derided as an art form. It is well to remember that for most of the 20th century, we have fostered a narrow view of the modernist period, one in which progressive modernism has received almost exclusive attention while conservative modernism has been largely ignored.

Conservative modernists, though, the so-called academic painters of the 19th and early 20th centuries, believed they were doing their part to improve the world. In contrast to the progressive modernists, conservative modernists presented images that contained or reflected good conservative moral values, or served as examples of virtuous behaviour, or offered inspiring Christian sentiment. Generally, conservative modernists selected subject matter that showed examples of righteous conduct and noble sacrifice that was intended to serve as a model which all good citizens should aspire to emulate.

Jean-Paul Laurens’s painting, Last Moments of Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico (1882; Hermitage, St. Petersburg), for example, shows the puppet emperor before his execution by firing squad in Querétaro, Mexico, on 19 June 1867. In contrast to Manet’s broadly painted, ‘unfinished’ picture, which depicts the event in unheroic terms and in a way that was construed by conservatives as critical of Napoleon III’s foreign policy (the painting drew official censorship as well as the disdain of conservative critics), Laurens presents the emperor as a noble hero, calmly consoling his distraught confessor while a faithful servant on his knees clings to his left hand. His Mexican executioners stand waiting at the door in awe of the emperor’s dignity and composure.

Édouard Manet

Execution of the Emperor Maximilian

1867, oil on canvas (Kunsthalle, Mannheim)

|

Jean-Paul Laurens

Last Moments of Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico

1882, oil on canvas (Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg)

|

Such treatment was seen by the progressives as uncritical and as merely supportive of the status quo; it offered a future that was little more than a perpetuation of the present. Conservatives generally wished to maintain existing institutions; any change would be brought about gradually. Progressives, on the other hand, were critical of institutions, both political and religious, because they were restrictive of individual liberty; they wanted radical change. Progressives placed their faith in the goodness of humankind, a goodness which they believed, starting with Rousseau in the 18th century, had become corrupted by such things as the growth of cities.

Others would argue that the rapid rise of industrial capitalism in the 18th century had turned man into a selfish, competitive animal whose inhumanity was increasingly apparent in the blighted landscape of the industrial revolution. Rousseau had glorified Nature, and a number of modernists idealized the country life. Thomas Jefferson lived in the country close to nature and desired that the United States be entirely a farming economy; he characterized cities as ‘ulcers on the body politic.’

In contrast to conservative modernism, which remained fettered to old ideas and which tended to support the status quo, progressive modernism adopted an antagonistic position towards society and its established institutions. In one way or another it challenged all authority in the name of freedom and, intentionally or not, affronted conservative middle-class values.

Generally speaking, progressive modernism tended to concern itself with political and social issues, drawing attention to troubling aspects of contemporary society, such as the plight of the poor and prostitution, which they felt needed to be addressed and corrected. Through their art, the progressives repeatedly pointed out political and social ills which an increasingly complacent and comfortable middle class preferred to ignore.

Fundamentally, the intention was to educate the public, to keep alive in the face of conservative forces the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and equality through which the world would be made a better place.

The position taken by progressive modernism came to be referred to as the avant-garde (a military term meaning ‘advance-guard’). In contrast to the conservative modernists who looked to the past and tradition, the avant-garde artist consciously rejected tradition. Rather than existing as the most recent manifestation of a tradition stretching back into the past, the avant-garde artist saw him- or herself as standing at the beginning of a new tradition stretching, hopefully, into the future. The progressive modernist looked to the future while the conservative modernist looked to the past.

Today, we would characterize progressive modernism, the avant-garde, as politically liberal in its support of freedom of expression and demands of equality. Since the 18th century, the modernist belief in the freedom of expression has manifested itself in art through claims to freedom of choice in subject matter and to freedom of choice in style in terms of choice of brushstroke and colour. It was in the exercise of these rights that the artist constantly drew attention to the goals of progressive modernism.

As the 19th century progressed, the practice of artistic freedom became fundamental to progressive modernism. Artists began to seek freedom not just from the rules of the Academy, but from the expectations of the public. It was claimed that art possessed its own intrinsic value and should not have to be made to satisfy any edifying, utilitarian, or moral function. In editorials in the influential review L’Artiste, the progressive French novelist and critic Théophile Gautier believed the idea that art should be independent, and promoted the slogan ‘l’art pour l’art.’ It was claimed that art should be produced not for the public’s sake, but for art’s sake.

Art for Art’s Sake was a rallying cry, a call for art’s freedom from the demands that it possess meaning and purpose. From a progressive modernist’s point of view, it was a further exercise of freedom. It was also a ploy, another deliberate affront to bourgeois sensibility. In his book, The Gentle Art Of Making Enemies, published in 1890, the progressive modernist painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler, proposed that ‘Art should be independent of all claptrap – should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye and ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. All these have no kind of concern with it.’

In his essay ‘The Soul of Man Under Socialism,’ published in 1891 in the Pall Mall Gazette, Oscar Wilde wrote:

A work of art is the unique result of a unique temperament. Its beauty comes from the fact that the author is what he is. It has nothing to do with the fact that other people want what they want. Indeed, the moment that an artist takes notice of what other people want, and tries to supply the demand, he ceases to be an artist, and becomes a dull or an amusing craftsman, an honest or a dishonest tradesman. He has no further claim to be considered as an artist.

However, Art for Art’s Sake was a stratagem that backfired. The same middle class whose tastes and ideas Whistler was confronting through his art, quickly turned the call of ‘Art for Art's Sake’ into a tool to further neutralize the content and noxious effects of progressive modernist art. From now on, art was to be discussed in formal terms — colour, line, shape, space, composition — which effectively removed the question of meaning and purpose from consideration and permitted whatever social, political, or progressive statements the artist had hoped to make in his or her work to be conveniently ignored or played down.

This approach became pervasive to the extent that artists, too, certainly the weaker ones, and even some of the strong ones as they got older or more comfortable, lost sight of their modernist purpose and became willy–nilly absorbed into this formalist way of thinking about art. In defense of this attitude, it was argued that, because the function of art is to preserve and enhance the values and sensibilities of civilized human beings, art should attempt to remain aloof from the malignant influences of contemporary culture which was becoming increasingly coarse and dehumanized.

Eventually there emerged the notion that modernist art is to be practiced entirely within a closed formalist sphere that was necessarily separated from, so as not to become contaminated by, the real world. The formalist critic Clement Greenberg, in an article first published in 1965 entitled ‘Modernist Painting,’ saw modernism as having achieved a self–referential autonomy. The work of art came to be seen as an isolated phenomenon governed by the internal laws of stylistic development. Art stood separate from the materialistic world and the mundane affairs of ordinary people.

The underlying assumptions at work here first of all posit that the visual artist, by virtue of special gifts, is able to express the finer things of humanity through a ‘purely visual’ understanding and mode of expression. This ‘purely visual’ characteristic of art made it an autonomous sphere of activity, completely separate from the everyday world of social and political life.

The self–determining nature of visual art meant that questions asked of it could be properly put, and answered, only in its own terms. Modernism’s ‘history’ was constructed through reference only to itself. Impressionism, for example, gains much of its art historical significance through its place within a scheme of stylistic development that has its roots in the preceding Realism of Courbet and Manet, and by its providing also the main impetus for the successive styles of Post-Impressionism.

In the hands of the conservative establishment, formalism became a very effective instrument of control over unruly and disruptive art. Many of the art movements spawned in the first half of the 20th century can be seen as various attempts to break the formalist grip on progressive modernism. The system, though, articulated by the more academic art historians and critics, operating hand–in–hand with the art market which was only interested in money and not meaning, effectively absorbed all attempts at subversion and revolt into a neutral, palatable, only occasionally mildly offensive history of art of the kind encountered today in art history textbooks.

Unfortunately for the history of art, in the process of neutralizing progressive modernism, art historians had to neutralize also all other art from earlier periods and from elsewhere in the world. The same reductionist approach was employed across the board creating a history of art largely devoid of any real meaning original to the artwork. It was generally agreed that aesthetic quality would have priority in deciding the function of art instead of its social or political relevance.

Formalism, though, could also be turned to the advantage of the progressives who were able to use it in defense of modernism, abstraction in particular, which has been especially open to criticism. Formalism also neatly dovetailed in the early 20th century with another goal of progressive modernism: universalism.

For art to be an effective instrument of social betterment, it needed to be understood by as many people as possible. But it was not a matter of simply manipulating images, it was the ‘true’ art behind the image that was deemed important. Art can be many things and one example may look quite different from the next. But something called ‘art’ is common to all. Whatever this ‘true’ art was, it was universal; like the scientific ‘truth’ of the Enlightenment. All art obviously possessed it.

Some artists went in search of ‘art.’ From an Enlightenment point of view, this was a search for the ‘truth’ or essence of art, and was carried out using a sort of pictorial reasoning. The first step was to strip away distracting elements such as recognizable objects which tended to conceal or hide the common ‘art’ thing.

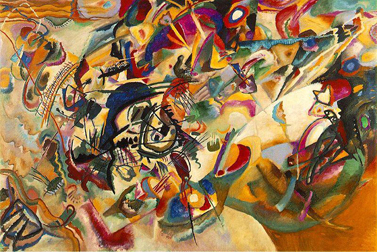

An example of this approach would be the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky who, in his Composition VII, for example, painted in 1913 and now in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, reduced his compositions to arrangements of colours, lines, and shapes. He believed colours, lines, and shapes could exist autonomously in a painting without any connection to recognizable objects.

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII

1913, oil on canvas (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

|

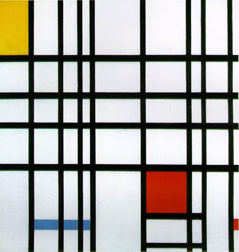

A more radical approach was to reduce the non-recognizable to the most basic colours, lines, and shapes. This was the approach of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian in his Composition with Yellow, Blue, and Red, for example, painted in 1921 and now in the Tate Gallery, London, in which three colours plus black and white are arranged as rectangular shapes in a grid.

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Yellow, Blue, and Red

1921, oil on canvas (Tate Gallery, London)

|

However, it is sometimes overlooked that for the artists who undertook this search, there was more at stake than the discovery of the ‘truth’ of art. For some, abstraction was a path to another goal. Both Mondrian and Kandinsky were keenly interested in the spiritual and believed that art should serve as a guide to, or an inspiration for, or perhaps help to rekindle in, the spectator the spiritual dimension which they and others felt was being lost in the increasingly materialist contemporary world. Abstraction involved a sort of stripping away of the material world and had the potential of revealing, or describing, or merely alluding to the world of the spirit.

New approaches to form and content were also being explored in music and literature. The French composer Claude Debussy explored unconventional harmonies in short compositions such as Prélude à l'après–midi d'un faune (influenced by Stéphane Mallarmé’s Symbolist poem), first performed in 1894, in which emphasis is placed on musical sound and tonal quality. In 1912, Debussy’s piece was made the basis for a ballet choreographed and performed by the Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky for the Ballets Russes in Paris. The following year, Nijinsky choreographed and danced in the ballet Le Sacre du Printemps by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, which, in its complex rhythmic structures and use of dissonance, together with Nijinsky’s radically unconventional choreography, shocked and scandalized both conservative critics and the public. The event, though, established the basis for developments of modernism in music.

As in the visual arts, music also became less ‘representational’ and evocative (that is, associated with real–world themes, events, places, people, objects, ideas, or emotions) and more abstract and expressive. The Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg pioneered atonality, in which music is composed without a tonal centre or key, and later, in the early 1920s, developed the dodecaphonic or twelve–tone technique of composition.

By this time, the supporters of progressive modernism had triumphed over the forces of conservative modernism. For the next fifty years, the ideals and practices of progressive modernism dominated European and American history.